Generating

legal possibilities

Helping private businesses dominate the field and win.

Elite legal services for business.

VETERANS IN HIGH-STAKES LITIGATION AND COMPLEX TRANSACTIONS FOR BUSINESS.

BUILD

We help operators start, fund, and expand their businesses with less risk, and from a position of power.

OPERATE

We find and fix vulnerabilities that can cost your business, from compliance to contracts.

GROW

We guide businesses through mergers, acquisitions, and other transactions, so they have a deal-table advantage, at-home and abroad.

FIGHT

We pursue justice on your behalf, inside and outside the courtroom, whether it’s recovering money you’re owed, enforcing your rights, or defending against threats.

Champions of business in complex environments.

We embrace thorny legal matters other firms are afraid to touch. Across employment law, contracts, litigation, intellectual property, mergers and acquisitions and real estate, we welcome new frontiers and think beyond the current case to drive resolution and set-up future wins.

ELITE OPERATORS

for high-stakes

Attacking problems head-on and finding leverage fast.

AGILE THINKERS

for complex issues

Blazing new roads and removing the obstacles.

SAVVY PLAYERS

for global business

Opening doors, seeing around corners, and setting up wins.

SEIZING OPPORTUNITIES. GENERATING ADVANTAGE.

Giving you the upper hand.

Firms like to talk about their “practice areas.” But we know clients don’t need “practice areas,” they need pragmatic solutions. Unlike our peers, we don’t box ourselves into neatly-defined categories, and stay in those lanes.

We help our clients win in their businesses, wherever they need us. Below are some of the ways we do that.

High-stakes litigation

A relentless champion for

your cause, no matter how

many zeros are involved.

Growth planning

Build a roadmap for mergers, acquisitions, and world domination.

Cross-border strategy

Legal sherpas to guide you in your global business journey.

Internal investigations

Get on the offense, and know your exposure.

Crisis management

Protect your reputation, negotiate, and rebuild.

Emerging tech

Helping companies in breakthrough industries navigate legal uncertainty

and change.

Outside General Counsel

Cost-effectively integrate seasoned counsel into your company’s day-to-day.

High-stakes litigation

A relentless champion for your cause, no matter how many zeros are involved.

Growth planning

Build a roadmap for mergers, acquisitions, and world domination.

Cross-border strategy

Legal sherpas to guide you in your global business journey.

Internal investigations

Get on the offense, and know your exposure.

Crisis management

Protect your reputation, negotiate, and rebuild.

Emerging tech

Helping companies in breakthrough industries navigate legal uncertainty

and change.

Outside general counsel

Cost-effectively integrate seasoned counsel into your company’s day-to-day.

No idea wtf is going on?

We fix that, too. Have something in mind that’s pioneering or unprecedented? Bring it on.

Embracing the challenges you face. Delivering the breakthroughs you need.

Get world-class attorneys on the matter – who will pick up the phone when you call, and champion your cause full-stop.

We proactively push your case and approach legal problems as opportunities to create advantage.

Talk to an attorney who gets it.

With us there is always a way. Get an experienced attorney at-your-

back and on-your-side, bringing full firepower to solve your problems.

With us there is always a way. Get an experienced attorney at-your-back and on-your-side, bringing full firepower to solve your problems.

It's different with us.

Many of our clients have worked with a firm (or a few) before they find us, and they are often discouraged by the results and experience.

We hold ourselves to a higher standard, and provide a different experience at Campbell Teague.

Many of our clients have worked with a firm (or a few) before they find us, and they are often discouraged by the results and experience. We hold ourselves to a higher standard, and provide a different experience at Campbell Teague.

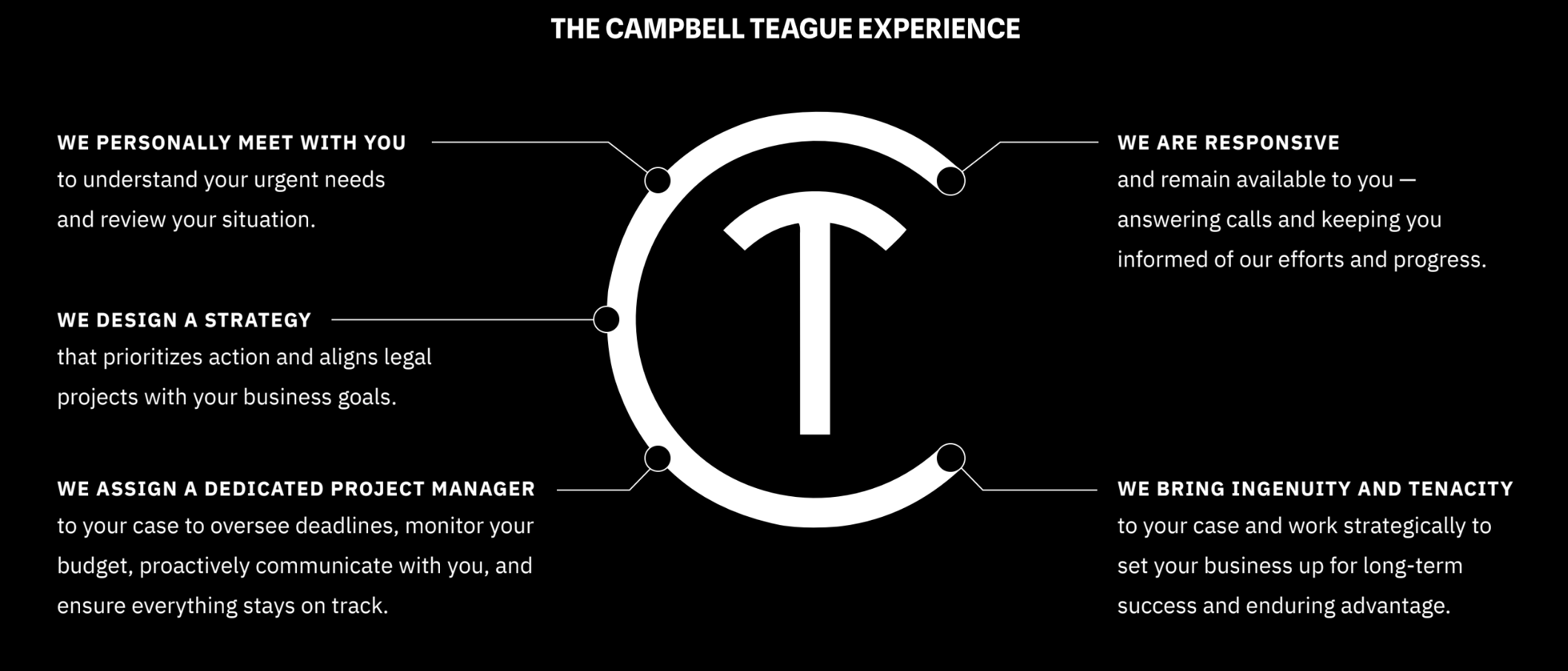

The Campbell Teague Experience

We personally meet with you

to understand your urgent needs and review your situation.

We design a strategy

that prioritizes action and aligns legal projects with your business goals.

We assign a dedicated

project manager

to your case to oversee deadlines, monitor your budget, proactively communicate with you, and ensure everything stays on track.

We are responsive

and remain available to you — answering calls and keeping you informed of our efforts and progress.

We bring ingenuity and tenacity

to your case and work strategically to set your business up for long-term success and enduring advantage.

Let us earn your trust.

Other firms will put your file on a stack and only call you back when it’s convenient. With us, you’re always top of mind.

Insights from our attorneys.

FEATURED ATTORNEY QUESTIONS:

Question: How do I protect my business against the risk that my bank could collapse?

Jordan’s Answer: We recommend thinking about three possible options, including multiple accounts, sweep accounts, and crypto self-custody.

Question: What the hell is a PIIA, and do I need one?

Leigh’s Answer: A PIIA ensures your company owns the IP your employees, contractors, and advisors make on your behalf. If you don’t have signed PIIAs, then you may not own what you think you do.